2017 Christmas Ornament

25 Dec 2017 in Electronics (Reading time: 3 minutes)After playing around with a custom DEF CON badge, I wanted to do another electronics project just for fun. What better time to share electronics with others than Christmas? So I decided to do a custom ornament for friends and family.

Though it shared some characteristics with my DEF CON badge (blinken lights, battery powered, etc.), the similarities ended there. In this case I want something lightweight (it’s going on a tree branch), simple (the XXV badges took a long time to assemble by hand), and that could run off a coin cell battery for days.

Not being the most artistic of individuals, I went with a simple snowflake design and 6 LEDs at the points. At first, I wanted to do white LEDs, but since they have a forward voltage around 3.2V, that wouldn’t work well with a single 3V coin cell, so I settled for 1.8V Red LEDs. (The battery will be unable to produce much current at all long before it reaches 1.8V.)

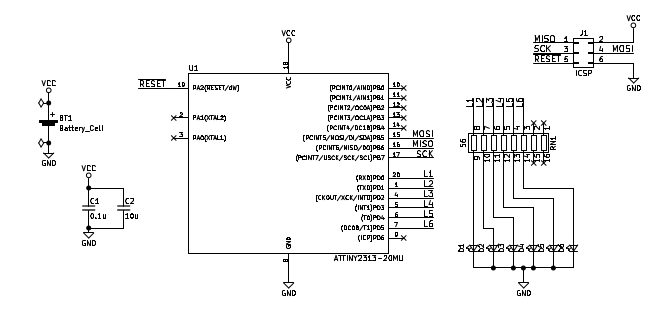

The ornament base is a red soldermask PCB with gold-plated (ENIG) copper. The boards were produced at Elecrow and I hand assembled the parts. The microcontroller is the ATTiny2313A, chosen both for low power consumption and low cost. (Driving 6 LEDs doesn’t take much in the way of CPU.) I chose not to use the ATTiny25/45/85 series because I didn’t want to deal with multiplexing pins to drive the LEDs and in-circuit programming (ICSP) header.

The schematic is pretty straight forward. There’s a battery holder and a couple of power supply capacitors (due to PWM of the lights, I didn’t want the input voltage bouncing around too much), the microcontroller, a single resistor network, and the 6 LEDs which are on the front of the board. The full bill of materials includes:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Label Description

---------------------------------------------------------------

BT1 20mm SMD Coin Cell Holder

C1 0.1uF Ceramic Capacitor (0805)

C2 10uF Ceramic Capacitor (0805)

U1 ATTiny2313A (QFN20)

RN1 Resistor Network, 8 Independent, 100 Ohm Each

D1-D6 Red SMD LED (0805)

J1 2x3 Header, SMD, 2.54mm Spacing (AVR ICSP)

On the actual ornaments, the ICSP header is unpopulated – I manually held a connector to it to program each one. I left the connector in a standard format instead of a pogo pin arrangement in case any of my recipients wanted to hack on the firmware. (Since it’s Open Source.)

It was a fun little project and I’m already considering how I can improve for a new one next year. Full schematics, design files, and source code are on Github.

[CVE-2017-17704] Broken Cryptography in iStar Ultra & IP ACM by Software House

18 Dec 2017 in Security (Reading time: 3 minutes)Introduction

Vulnerabilities were identified in the iStar Ultra & IP-ACM boards offered by Software House. This system is used to control physical access to resources based on RFID-based badge readers. Badge readers interface with the IP-ACM board, which uses TCP/IP to communicate with the iStar Ultra controller.

These were discovered during a black box assessment and therefore the vulnerability list should not be considered exhaustive; observations suggest that it is likely that further vulnerabilities exist. It is strongly recommended that Software House undertake a full whitebox security assessment of this application. Additionally, it is our suggestion that all communications be conducted over TLS. While alternatives are suggested below, cryptography is very difficult even for experts, and so using a well-understood cryptosystem like TLS is preferable to home-grown solutions. The version under test was indicated as: 6.5.2.20569. As of the time of disclosure, the issues remain unfixed.

Issues Found

The communications between the IP-ACM and the iStar Ultra is encrypted using a fixed AES key and IV. Each message is encrypted in CBC mode and restarts with the fixed IV, leading to replay attacks of entire messages. There is no authentication of messages beyond the use of the fixed AES key, so message forgery is also possible. A working proof of concept has been demonstrated that allows an attacker with access to the IP network used by the IP-ACM and iStar Ultra to unlock doors connected to the IP-ACM. (This PoC will not be disclosed at this time, due to the issue remaining unfixed.)

Impact & Workaround

An attacker with access to the network can unlock doors without generating any log entry of the door unlock. An attacker can also prevent legitimate unlock attempts. Organizations using these devices should ensure that the network used for IP-ACM to iStar Ultra communications is not accessible to potential attackers.

Timeline

- 2017/07/01-2017/07/14 - Issues discovered

- 2017/07/19 - Issues disclosed to Software House

- 2017/08/29 - Issues acknowledged & proposed fixes discussed. Informed that current hardware could not be fixed and fixes would only apply to new products.

- 2017/10/19 - 90 day window elapsed in accordance with disclosure policy.

- 2017/12/18 - Public disclosure.

Credit

These issues were discovered by David Tomaschik of the Google Security Team.

2017 Hacker Holiday Gift Guide

22 Nov 2017 in Misc (Reading time: 15 minutes)I’ve been thinking about gifts for Hackers and Makers lately as the holiday season arrives. I decided I’d build a public list of some of my favorite things (and perhaps some things I’d like myself as well!) I’ll break it down into a few categories for different kinds of hackers (and different kinds of gifters as well). Prices are current as of writing, but not something I’ll be updating.

Hardware Hacking, Reversing and Instrumentation: A Review

11 Nov 2017 in Security (Reading time: 4 minutes)I recently attended Dr. Dmitry Nedospasov’s 4-day “Hardware Hacking, Reversing and Instrumentation” training class as part of the HardwareSecurity.training event in San Francisco. I learned a lot, and it was incredibly fun class. If you understand the basics of hardware security and want to take it to the next level, this is the course for you.

The class predominantly focuses on the use of FPGAs for breaking security in hardware devices (embedded devices, microcontrollers, etc.). The advantage of FPGAs is that they can be used to implement arbitrary protocols and can operate with very high timing resolution. (e.g., single clock cycle, since it’s essentially synthesized hardware.)

The particular FPGA board used in this class is the Digilent Arty, based on the Xilinx Artix 7 FPGA. This board is clocked at 100 MHz, allowing 10ns resolution for high-speed protocols, timing attacks, etc. The development board contains over 33,000 logic cells with more than 20,000 LUTs and 40,000 flip-flops. (And if you don’t know what those things are, don’t worry, it’s explained in the class!) The largest project in the class only uses about 1% of the resources of this FPGA, so there’s plenty for more complex operations after the class.

Dmitry is obviously very knowledgable as an instructor and has a very direct and hands-on style. If you’re looking for someone to spoon feed you the course material, this won’t be the course you’re looking for. If, on the other hand, you prefer to learn by doing and just need an instructor to get you started and help you if you have issues, Dmitry has the perfect teaching style for you.

You should have some knowledge of basic hardware topics before starting the class. Knowing basic logic gates (AND, OR, NAND, XOR, etc.), basic electronics (i.e., how to supply power and avoid short circuits), and being familiar with concepts like JTAG and UARTs will help. I’ve taken several other hardware security classes before (including with Joe Fitzpatrick, another of the HardwareSecurity.training instructors and organizers) and I found that background knowledge quite useful. If you don’t know the basics, I highly reccommend taking a course like Joe’s “Applied Physical Attacks on Embedded Systems and IoT” first.

The first day of the class is mostly lecture about the architecture of FPGAs and basic Verilog. Some Verilog is written and results simulated in the Xilinx Vivado tool. Beginning with the second day, work moves to the actual FPGA, beginning with a task as “simple” as implementing a UART in hardware, then moving to using the FPGA to brute force a PIN on a microcontroller, and finally moving on to a timing attack against the microcontroller. Many of the projects are implemented with the performance-critical parts done in Verilog on the FPGA and then communicating with a Python script for logic & calculation.

I really enjoyed the course – it was challenging, but not defeatingly so, and I learned quite a few new things from it. This was my first exposure to FPGAs and Verilog, but I now feel I could successfully use an FPGA for a variety of projects, and look forward to finding something interesting to try with it.